UCGHI researchers will play a lead role in educating the next generation of the global health workforce in one health approaches through winning up to $85 million over five years from USAID.

The One Health Workforce—Next Generation Project is led by the One Health Institute at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Woutrina Smith, Associate Director of the One Health Institute and the Co-Director of the UCGHI Planetary Health Center of Expertise, is the Principal Investigator. The project leadership team includes Jonna Mazet, Executive Director of the One Health Institute, who led an earlier related project; Ndola Prata, Co-Director of the UCGHI Women’s Health, Gender and Empowerment Center of Expertise and a Professor of Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health at UC Berkeley; and Oladele Ogunseitan, a member of the UCGHI Board of Directors and founding chair of the Department of Population Health and Disease Prevention at UC Irvine.

The term “One Health” was coined to convey that human health isn’t isolated from animal and plant health and the environment all rely on. One Health has always been part of the UCGHI approach, said Pat Conrad, Co-Director of UCCHI.

The USAID award “is a clear and outstanding example of the benefits of UCGHI in bringing our global health faculty from the different campuses together and of our Centers of Expertise collaborating,” said Pat Conrad. “It made for a very powerful application.”

The project includes additional researchers across the UC system as well as from Columbia University, EcoHealth Alliance, Ata Health Strategies, the University of New Mexico, and Sandia National Laboratories. The U.S. researchers will work with One Health Central and Eastern Africa (OCHEA, soon to be known as AFROHUN) and the South East Asia One Health University Network (SEAOHUN) to strengthen these networks of universities, and to create sustainable programs to develop a workforce of well-trained in One Health principles.

This will be crucial to addressing emerging human health issues, Smith said. “One Health is a team approach to solving problems that works across sectors and across disciplines. We need that sort of collaborative team environment for the most innovative problem-solving in the future,” she said.

“The diseases we work with evolve, and increasingly move between people and animals. If doctors and veterinarians don’t communicate, they won’t be able to quickly identify a disease outbreak or understand what recommendations to give people to prevent a disease from spreading,” she said.

Smith feels the project is a logical next step following PREDICT, a 10-year, $185-million USAID project that she and other UCGHI researchers worked on. Originally led by Mazet, the new workforce project’s Project Director, PREDICT’s focus was to identify and prevent possible transmissions of zoonotic viruses in Africa and Southeast Asia. Because PREDICT included some of the same partners in the regions, its researchers are already well-connected for the current project, she said.

“That was partly why I was excited to lead this new initiative,” Smith said. “It helps to really build the partnerships and the programs that we’d started, to grow further into a stronger regional approach.”

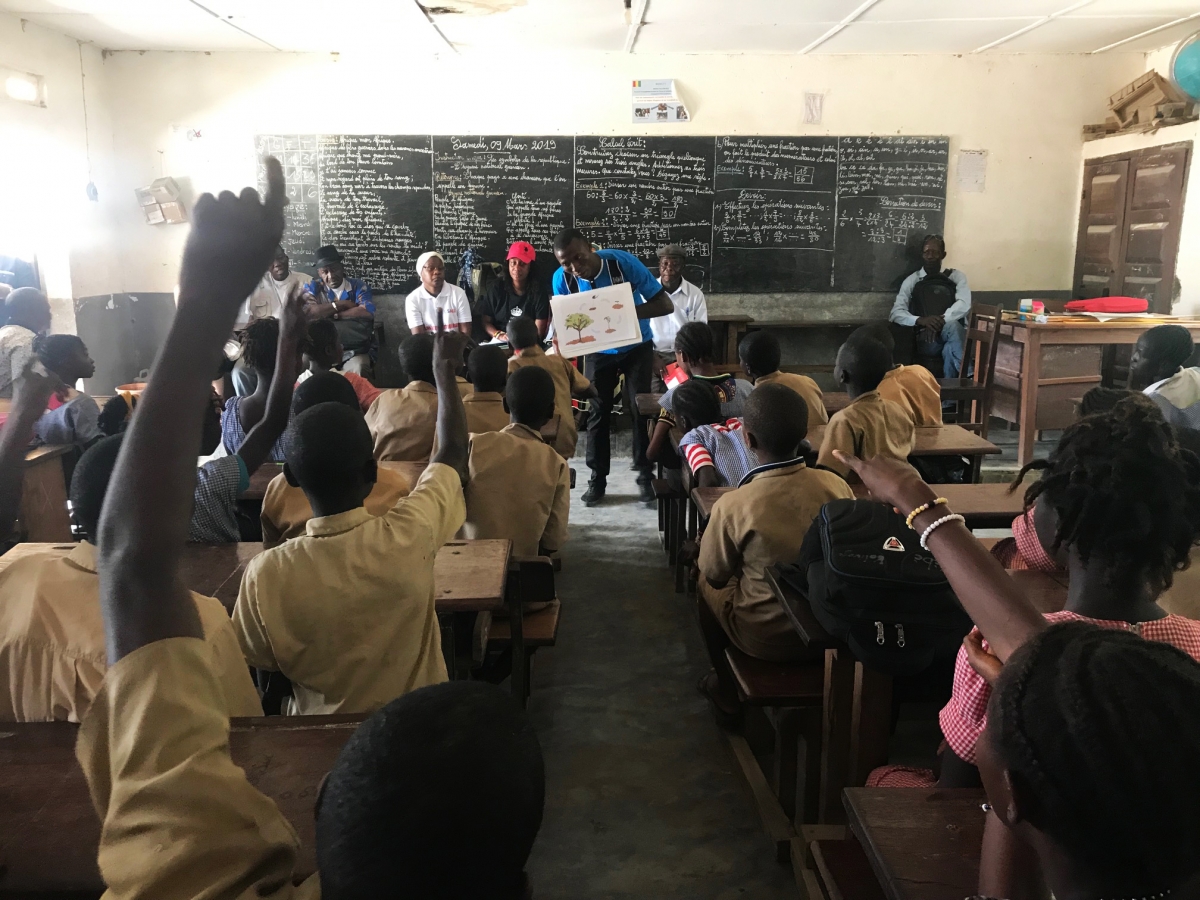

Instead of a focus on viral discovery and outbreak response as in PREDICT, the workforce project is “more focused on training the next generation of professionals so that they are ready to lead these important efforts in their home countries for the long run,” she said.

The project has three objectives to achieve this: training and empowerment, workforce tracking and assessment, and empowering the regional networks to become self-sustaining.

Over the past decade, the most workforce development scope supported by USAID has been focused on the first objective, which is now being led by Ogunseitan. The process is beginning with developing or curating existing One Health courses and modules and filling competency gaps in workforce training, both for those who are currently in enrolled in the universities and also for working professionals, he said.

What distinguishes a one health educational approach from single discipline training programs is the need to recognize the variety of disciplines crucial to solving problems, Ogunseitan said. Frontline health workers, like physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and public health practitioners, are one group of disciplines. Veterinary medicine is another. Environmental disciplines are another important component of one health that have until recently been underdeveloped, he said.

Antibiotic resistance is a flagship example of the need for one health workforce training, Ogunseitan said. Antibiotics revolutionized how medicine treated infectious diseases, but due partly to a lack of understanding of bacterial diversity and evolution have been used irresponsibly, he said. Antibiotics are overused not just in human medicine but in agriculture to increase meat production and treat plant bacterial diseases, he said.

“Now we’re recognizing that that’s a callous way of using antibiotics. But we are nowhere near controlling the situation,” he said.

A recent report from United Nations and other international experts estimates that by 2050, drug-resistant infections could cause 10 million deaths globally each year.

Many disciplines must be involved to solve the problem, Ogunseitan said. Physicians must be trained not to overprescribe antibiotics, patients must be taught not to demand antibiotics for diseases that antibiotics won’t help, and governments must establish better controls on wastewater discharge and agricultural use, he said.

Case studies are essential to address this interconnectedness, Ogunseitan said. Many existing case studies are available to learn from, but virtual technology will also be used to develop scenarios so that trainees can imagine themselves in situations where they have to work with other professionals to respond, he said. Field work will also be important, he said.

“This is a new kind of educational program that addresses the multiple disciplines involved with real-life scenarios and team activities that allows us to foster a workforce that’s ready to prevent and respond,” to outbreaks, he said.

Part of the USAID funding will go to establishing virtual communities of practice using the ECHO model. The model was developed by a team at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, members of whom are on the workforce project team. A “hub” of multidisciplinary faculty members, researchers, and practitioners will be trained in different skills. They will then return to their universities as spokes of the hub to start their own hubs to train others.

For areas where diagnosing a condition is difficult, the virtual communities could provide a lab training component to quickly train people in diagnosis techniques as well as offer a way to reach out globally for help.

Rather than work on the three objectives objective by objective, all are active at the same time, Smith said. During the first few years, the team will work very closely with the regional networks on conducting their trainings as well as on improving their business practices, Smith said.

For the training and empowerment objective, “when we get to the point where people who are trained in the one health approach are employed in government agencies, the private sector, and other public sectors, where they are the decision makers or tightly connected to decision makers on how to prevent disease and to respond to disease, then we would have reached our goal,” Ogunseitan said.

Smith said that for the second objective, the U.S. team led by Columbia University’s ICAP Program will help the regional university networks advance in managing data and assessing One Health competencies. A goal of the third objectives is that by Year 3 or 4, the university networks should be able to compete for and administer donor funding to continue the programs more independently. The journey to self-reliance is really the USAID focus,” Smith said.